WOMEN AND BULLFIGHTERS: FROM BLEACHERS TO ALCOVE

“We Spaniards have mass in the morning, bullfighting in the afternoon and a brothel in the evening. What does it all blend into? In sadness.”

André Malraux La Tête d’Obsidienne, 1974

In Picasso’s work, the female bullfighter first appears in scenes inspired by observed reality. In the arena, she is a spectator, sympathizing with or admiring the picador or matador, without the bull, the central actor, attracting the young artist’s attention.

By the end of the 18th century, the matador had become a paragon of seduction, often depicted in gallant company. In Malaga, in the house where Picasso was born, a small oil painting can still be seen adorning the family living room: a bullfighter playing the pretty heart to beautiful women in mantillas. This painting bears witness to the cultural environment in which Picasso grew up, marked by costumbrismo – an artistic movement concerned with the representation of customs and mores – the imprint of which would live on in the artist’s productions. Scenes in which the woman is the object of seduction and the fighter the object of admiration and desire can be found as much in folk art or in the Hispanic imagery of French Romanticism as in Picasso’s contemporaries, such as Zuloaga, or today in the montages of Christian Milovanoff.

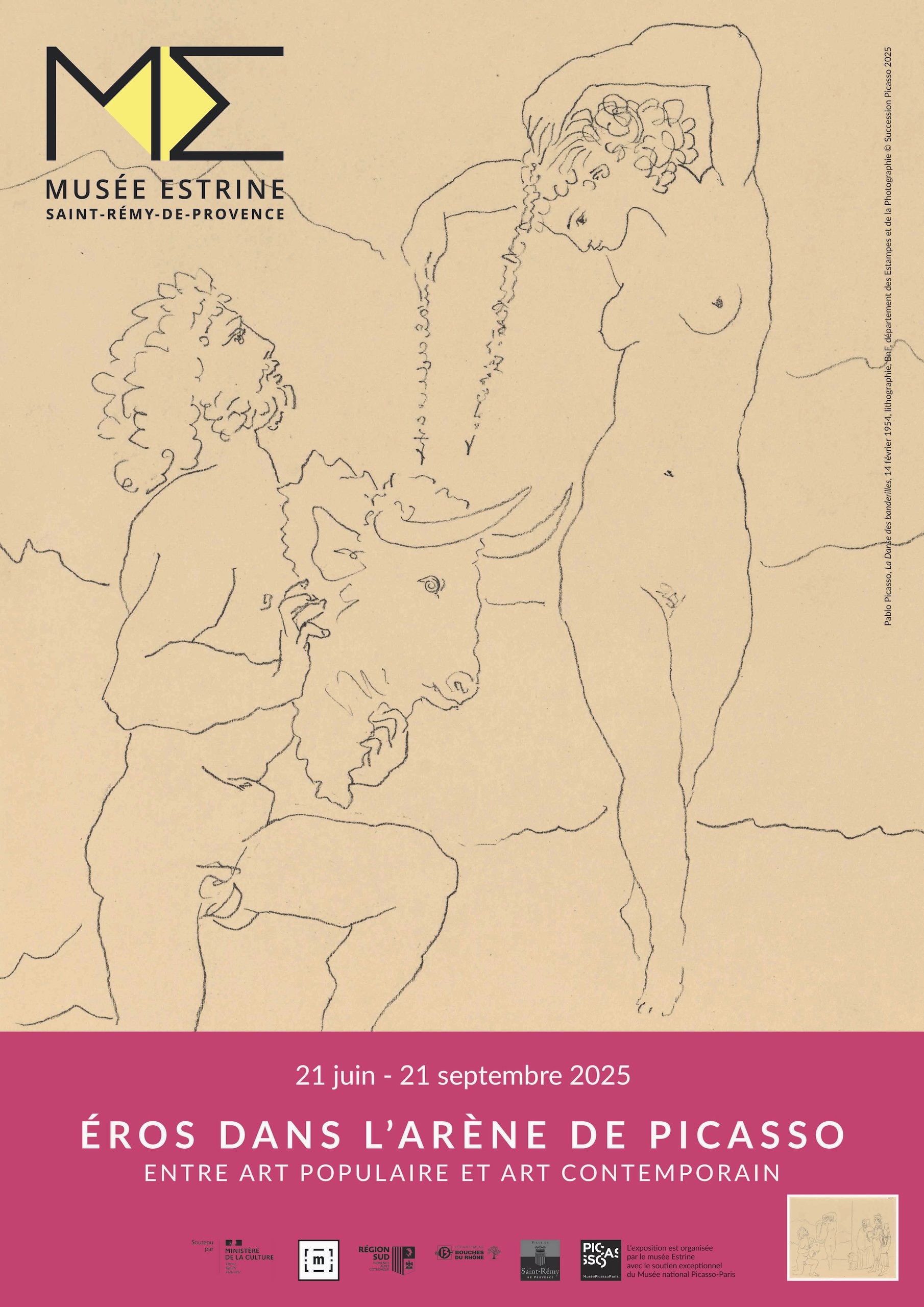

In old age, when he could no longer recognize himself in the bravery and power of the bull, Picasso evacuated his animal double. And if he returns to the fetish figure of the picador, it’s not in triumph over his adversary under the sun of the arena, or the compassionate gaze of women, but haunting brothels, more voyeur than consumer. Eroticism is no longer to be found in the sublimated body-to-body encounter between beast and man, or between woman and her half-man, half-bull partner, but in the misguided encounter authorized by paid love.